The Chinese or Lunar New Year seems to be a bigger deal this year. Previously, you didn’t seem to hear about it as much on social media, on TV or when you looked it up on certain search engines (worth it for the fireworks). I can only conclude that this is because it’s the Year of the Tiger. Tigers are appealing. Tigers are cool. They’re rare, a bit mysterious, they’re exotic & can easily be made into cute cartoons. Visually, they’re incredible. Last year was the Year of the Ox. No disrespect to any oxen out there but you can see what I’m driving at. A tiger is one of what’s known as “charismatic megafauna,” in other words, it is large, recognisable, has widespread cultural significance or has some symbolic importance.

Tiger woodcut by Franz Marc (1912)

According to the Chinese Zodiac, someone born this year can expect to be brave, pleasant & ambitious. I suppose we can only hope that they grow up to use these traits for the good of the world, no matter how great they might look…

David Mach’s M&S teacake wrapper tiger of 2012(?)

This week I’ve trawled the art world for its perceptions of the mighty tiger & as ever there were plenty. Whether it’s a woodcut by Marc or Mach’s tiger made of rubbish one hundred years later, the tiger is an irresistible subject. (Warning: sometimes the results are entirely resistible).

Maruyama Okyo, Sitting Tiger (1777)

There’s no doubt he’s the king of the beasts, yet there’s something more in his expression. Disgruntled? Perhaps he’s just found out he’s been awarded only third place in the Great Race across the river; won by clever Rat, second place given to hard-working Ox, the Great Race legend gives us the Chinese Zodiac, with each creature teaching us a lesson about how to live & explaining our nature. Poor old Tiger had expected to win but as is all too often the case in the animal-fable world, he’s reduced to a morality figure.

Franz Marc, Tiger (1912)

Marc never fails to find the gentle beauty in all nature, depicting a tiger just as sensitively as his horses. Here he creates an impression of forest & its accompanying light & shows the shyness of the tiger.

David Mach, Tiger (2012)

Look closely & you’ll see Mach’s tiger is made from wire coat hangers. As with his shiny wrapper tiger above, he frequently uses unusual & unexpected media to create his sculptures. They’re mass-produced items, on the face of it disposable - until he turns them into art. One wonders where he starts. Here he talks about using common materials, making works designed to annoy & how ideas are triggered for his installations & other pieces:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVGQ-PTsxs0

Eugène Delacroix, Young Tiger Playing With Its Mother (1830)

If you’ve ever seen social media sites focused on Bad Taxidermy, you might recognise their premise in Delacroix’s tigers. I’ve seen very badly stuffed tigers in museums & it's one of the most depressing things I’ve ever witnessed. I could be wrong, but I feel such unfortunates could have been the models for Delacroix’s wonky painting. Such amazing creatures being hunted to the verge of extinction for mere superstition & rugs is bad enough but then bestowing upon them the indignity of mis-stuffing their faces in particular is unforgivable. Conclusion: we’re a horrible species.

Henri Rousseau, Tiger in a Tropical Storm (Surprised!) (1891)

Highly stylised & almost visionary, Rousseau’s is probably one of the more famous tigers in art. He’s very focused on the head: the teeth, whiskers & eyes almost anthropomorphising the tiger in his shock (yes, I’d say “shocked” rather than “surprised”). Yet, a tiger must have been somewhat more used to living with these conditions. Anyway, I like the rest of the painting a great deal – the storm is depicted brilliantly. It’s quite subtle yet you’re transported there. It’s as if you can hear it, smell it.

Morris Hirshfield, Tiger (1940)

If I had to describe this monumentally ugly piece honestly yet politely, I’d say: a level of primitivism that’s hard to look at. But it’s not all about subjectivity. You might like it anyway. & what is Hirshfield trying to say? Well perhaps he’s emphasising the might of the tiger, the assertion in the Chinese myths that he was king of the jungle. Or perhaps he’d had one too many deer for breakfast. I feel like the only way we know this is a tiger is its pattern. Otherwise it could be any four-legged creature. Imagine it with cow print. It’s a cow. Imagine it with black & white stripes. It’s a zebra. & so on.

Peter Paul Rubens, Tiger, Lion & Leopard Hunt (1616)

Wow. This is exactly the type of overwrought & at best inaccurate tomfoolery that Rubens gets any bad press for. This lack of understanding of oh, I don’t know, geography, not to mention the nature of wild creatures is one of the reasons humans have decimated the natural world. Sadly, there are already animal casualties in this incredible painting, but it’s nice to see the tiger managing to make his point as strongly as he is.

William Blake, Tyger (1794)

As much as I love Blake, no.

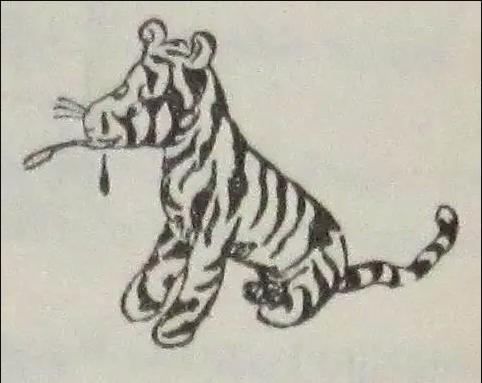

E.H. Shepherd, Tigger (1928)

Anthropomorphism is always a dangerous caper but E.H. Shepherd’s Tigger is based on a soft toy tiger – we can clearly see this from the first drawing – so it doesn’t really count. This is Tigger the toy drawn “from life.” A.A. Milne’s book character is of course completely & gloriously daft as a brush, memorably boundless in energy & entirely unencumbered by wit.

Peter Howson, Tiger (2000)

What I think is great about Howson’s tiger is the timidity & shyness evoked in its expression & movement. The tiger lopes out of the darkness & appears startled by our presence. Unfortunately, there is evidence of injury, but the drops of blood are almost like stigmata rather than the result of a fight. Is Howson trying to portray the sacrifice tigers have made for our greed & stupidity?

No comments:

Post a Comment